America Succeeds defines Leadership as the ability to inspire, guide, and influence others toward achieving shared goals while demonstrating integrity, adaptability, and collaborative decision-making. This encompasses self-awareness, communication excellence, strategic thinking, and the capacity to mobilize diverse groups around common purposes.

Picture Nick, seventeen years old, standing before One Stone’s board of directors with a financial presentation tracking $2.1 million in assets. His hands are steady as he navigates complex spreadsheets, fielding questions from adult board members who lean forward, taking notes. Later, staff members would whisper: “If he presented that to C-level executives, it wouldn’t be out of place.”

Meanwhile, in rural Indiana, Abi addresses the State Board of Education about work-based learning’s transformative impact. Four years earlier, she was a quiet freshman recovering from a concussion, unsure of her place beyond the family farm. Now she leads a business grossing over $200,000 annually, presides over the FFA chapter, and advocates for educational innovation at the state level. “I can do my thing,” she declares with hard-earned confidence.

These transformations weren’t accidental—they were systematic. While many schools confine leadership to student government elections or hope it emerges naturally through group projects, One Stone and Batesville High School discovered that authentic leadership develops through three interlocking practices: making leadership skills explicit and visible, engaging students in experiences with genuine responsibility, and integrating leadership development throughout all learning. When these practices work in concert—rather than as isolated activities—they create a multiplier effect transforming hesitant followers into confident leaders who create lasting change.

One Stone: Leadership Through Radical Trust and Real Responsibility

Nick’s experience wasn’t a simulation. These are real dollars, real decisions, with real consequences. Welcome to leadership development at One Stone, a tuition-assisted independent high school in downtown Boise, Idaho, that revolutionizes education through radical student agency. Serving 100+ students, their learners engage in a variety of personal, community, and community-connected projects that support their development of 24 competencies through the lens of Stanford’s design thinking framework. What distinguishes One Stone perhaps even more is the fact that two-thirds of its board are students, and students run a number of One Stone’s enterprises including Two Birds (a marketing and social media group) and Project Good (which supports and organizes a variety of social projects for good). As they say, they work to support the development of “better leaders and the world a better place.”

At One Stone, leadership isn’t left to chance or natural talent—it’s named, tracked, and celebrated in every corner of the school. Walk through the building and you’ll see the “Disruption Blob,” a vibrant visual framework where “LEADERSHIP” sits boldly alongside “PASSION” and “OWNERSHIP.” These aren’t motivational posters; they’re living vocabulary that both educators and students use daily.

Ava’s transformation makes this visibility clear. Two years ago, when she arrived from homeschooling, her advisor Camille recalls that she was “deeply questioning her ability to show up in this space.” But One Stone made her leadership growth explicit. When Ava led her first building tour, coaches didn’t just say “good job”—they identified specific competencies, such as “stakeholder engagement,” “organizational representation,” “public speaking under pressure.” And by senior year, Ava stood on the main stage at One Stone’s annual showcase event, addressing hundreds. The girl who once doubted herself now led Mindful Mornings mental health groups, and had organized several community initiatives, led the school’s “do good team” service group, coordinated weekly community clean-ups, and served as a student ambassador who guided prospective families through tours of One Stone’s innovative learning spaces. As Camille, her advisor put it, she “will jump in and lead” anywhere she’s needed. This transformation happened because every small act of leadership—from facilitating a reflection circle, to organizing community clean-up teams, to leading several community intitative—was explicitly identified, recognized, and lifted up as leadership in action.

But real leadership can’t be simulated—it emerges when stakes are genuine and communities depend on you. Freshmen begin with simple acts through X-Lab, their exploration year: organizing supplies for a community music festival, co-leading reflection circles, participating in Project Good service initiatives where they fold towels during community clean-up—what Ava called “10 minutes of quiet magic” that builds relationships and confidence. But coaches ensure they recognize these as leadership foundations: “event coordination,” “group facilitation,” “emotional intelligence in action.” Even these small responsibilities matter when real community events depend on student organization.

Sophomore and junior years bring D-Lab complexity, where students manage team dynamics on real client projects. Kai evolved here from someone whose communication seemed “demanding and rude” to discovering what her educator called “the magical formula”—knowing when to support struggling teammates versus when to challenge them toward growth. Students lead design thinking sessions with community partners, facilitate ideation workshops, manage project timelines. These middle years press students to navigate personality conflicts, balance diverse perspectives, and adapt their leadership style to different contexts—all while delivering real solutions to real organizations.

Senior year, students pursue their own Y-Labs, independent “doing good in the world” leadership projects. Students identify their community partners, co-define the problems they want to pursue, and manage all of the activities they need to engage in their solutions. Willow worked “entirely alone by choice” to save Sweet Soulless Candy, a non-profit candy store that employed disabled adults, raising $18,000 through social media and flyers, managing every aspect of the campaign. These aren’t assigned projects but self-initiated missions where students own every dimension of leadership from vision to execution.

The progression is deliberate: from following established protocols to creating new systems, from co-leading with support to leading independently, from managing tasks to managing complexity. Each year adds layers—broader stakeholder groups, higher stakes, more autonomy—until seniors like Nick manage $2.1 million budgets and deliver financial presentations that staff call worthy of “C-level executives.”

Such experiences, inclusive of their advisors’ guidance and mentorship, press One Stone students’ development of leadership skills as a result of having to orchestrate collaboration between corporate executives and food bank directors, to finding a solution to keep a non-profit from going under, to managing the policies, funding, and activities of their own school.

Finally, One Stone integrates leadership development throughout every experience through sustained advisor relationships and systematic reflection. Willow describes how mentors meet with students “weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly, to talk about their schooling, any goals they have, how they’re doing… the ways that they want to grow.” These aren’t casual check-ins but structured conversations where advisors help students recognize the leadership capabilities emerging from their experiences. When Camille watched Ava evolve from “deeply questioning her ability” to confidently saving a business, she helped Ava understand she was practicing “project management” and “community organizing.” When Julia observed Kai discover the “magical formula” for supporting teammates, she named this as “adaptive leadership”—making it a transferable skill rather than just an intuitive feeling. The BLOB framework (Bold Learning OBjectives) makes this integration even more visible, where students are asked to track their leadership development alongside 23 other competencies in their learner growth transcripts.

As One Stone’s principal, Michael Reagan, observes: “We don’t teach leadership through lectures. We create conditions where leadership becomes necessary, then support students as they step into it.” Through this integration—where every project demands leadership, every advisor conversation names it, and every reflection deepens understanding—One Stone transforms leadership from something students learn about into something they embody.

Batesville High School: Leadership Through Progressive Responsibility and Community Partnership

Abi’s transformation isn’t accidental. It’s the result of Batesville High School’s systematic approach to leadership development—one that serves 700+ students in rural Indiana through progressive responsibility, authentic community partnerships, and intentional self-discovery. As a Ford Next Generation Learning site, Batesville has spent years refining how traditional public schools can develop leaders who don’t just hold titles but create genuine impact.

At Batesville, leadership skills are explicitly identified and named through activities that make abstract competencies recognizable, discussable, and concrete. Freshmen lay the groundwork toward their leadership journey starting with identity exploration and foundational skills freshman year. Then all students’ complete DISC assessments sophomore year, followed by a continual review and reflection on those skills their junior and senior years. Unlike most personality tests filed away and forgotten, this work and the DISC assessment becomes what educator Allison describes as a living framework for helping their students understand their leadership skills: “We talk a lot about how they change based on your environment. So your natural style at home might be different from your adaptive style at school might be different from your adaptive style at work.”

Students don’t just learn leadership in abstract terms, they become “leaders” through a variety of opportunities, in the school, in their community, and in their work-based learning opportunities, discovering and discussing such specific leadership dimensions as Dominance, Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness. Brian, the Assistant Principal, says the school focuses on students’ “confidence, integrity, and authenticity,” and how they can grow everyday. He adds: “There is just the ability to be able to go into different environments and be appropriate, whether that be sitting in a meeting here with the five of us,and being able to go into a dialog and provide their expertise or their experience, but also be able to go out and then be a leader on the football team.” When Ed, the Work-Based Learning Coordinator, debriefs with students, he translates their experiences into professional language: “What a 17-year-old calls problem solving, the Work-Based Learning Coordinator calls continuous improvement, kaizen, adaptive thinking.” This explicit naming—displayed on walls, embedded in rubrics, woven into daily conversations, and emphasized throughout the various activities at the school—transforms vague aspirations into measurable competencies students can consciously develop.

At Batesville, real leadership emerges through authentic responsibility with genuine stakes, guided by industry experts and dedicated mentors who transform workplace experiences into leadership laboratories. The school deliberately chose the term “mentorship” over “internship” when students sign-up for and engage in their work-based learning opportunities to signal this deeper commitment. As one educator explained, when you hear the word internship you think of having a student do some work for you. But when you hear the word mentorship that means we are expecting someone to take a student under their wing and support their growth, focusing more on their relationship and personal guidance: “What we wanted is somebody to mentor our students. Somebody that can take our students into the fold and say, ‘This is what we do as a company, this is how you can be a part of it.'” This philosophy results in remarkable student leadership experiences. Under the music director’s guidance, Ethan’s senior year exemplifies the outcome of such mentoring: Ethan didn’t just observe or engage in small tasks related to music, he ended up leading elementary choirs, supporting fifth and sixth grade performances, directing his church’s youth choir, and taught private piano students. As Dan put it, “I feel like giving the students opportunities to be leaders, gives them the opportunity to take advantage of things for themselves, giving them the tools, and then giving them the real hands on opportunities to do that. I want them to be thinking for themselves and not having it always just spoon fed to them.”

The progression of authentic leadership experiences intensifies as students mature, with community partners and industry mentors scaffolding increasingly complex responsibilities. Nick’s journey at Batesville Tool & Die illustrates how workplace mentors develop leadership: starting with basic machining, he progressed to training newer employees, eventually earning a full-time position before graduation. “The true mentors have been the people teaching me how to run different equipment,” he reflects, but they taught him more than technical skills—they showed him how to take ownership, solve problems independently, and guide others.

Abi’s supervised agricultural experience through FFA—the first of its kind nationally—combined her family farm work with formal business development, mentored by both her ag teacher Cassie and industry professionals. Her progression from managing siblings in fields to presenting at National FFA Convention to advocating before state policymakers shows how authentic stakes accelerate leadership growth. Her agricultural work-based learning experience led to remarkable entrepreneurship, growing her business from $40,000 to over $200,000 in sales, with other students actually working for her. In the end, Abi said: “I would say leadership to me means being a personable person, that anybody can that anybody under you, or not necessarily that they’re under you, but they can look to you for advice, or you they can go you’ve gone through the same process as them, and you can just relate to them. I don’t think leadership means being the top dog all the time to where you’ve your head strong and you’re just telling people what to do. It’s not just a delegator. It’s being that person that people can look to for words of wisdom, for just help with something, or just that you’re inspiring them to get through their own journey.”

In the end, Batesville integrates leadership development into every aspect of their curriculum, instruction, and assessment, creating a coherent system where academic learning and leadership growth reinforce each other. The curriculum embeds leadership systematically across all four years: freshman seminar introduces foundational concepts; sophomore year deepens self-awareness through Student Resource Time (SRT) skills modules and DISC assessment activities; juniors engage in RISE leadership programming; and seniors apply everything through a variety of work-based learning opportunities. But leadership isn’t confined to designated programs. Jake observes: “In every class, you’re making presentations once or twice a year,” with teachers deliberately building leadership competencies into their subject matter. The engineering teacher creates YouTube videos used nationally, modeling how expertise becomes leadership. The government teacher runs election simulations where students manage campaigns, learning political leadership through practice. Even Spanish and ASL teachers integrate cultural leadership perspectives, showing students multiple ways to influence and inspire.

Instruction methods privilege active leadership practice over passive learning, with community members serving as co-educators who bring authentic assessment into the classroom. Sophomore mock interviews involve real community members who evaluate students using professional criteria. Junior RISE sessions bring industry leaders to coach specific competencies. Senior work-based learning transforms experiences into leadership laboratories where workplace supervisors become instructors. This integration ensures students don’t just learn leadership concepts but develop the muscle memory of leading through hundreds of authentic practice opportunities, each assessed not by artificial rubrics but by real-world impact on their businesses, their students, their patients, and their community.

The Multiplier Effect: Why Systematic Leadership Transforms

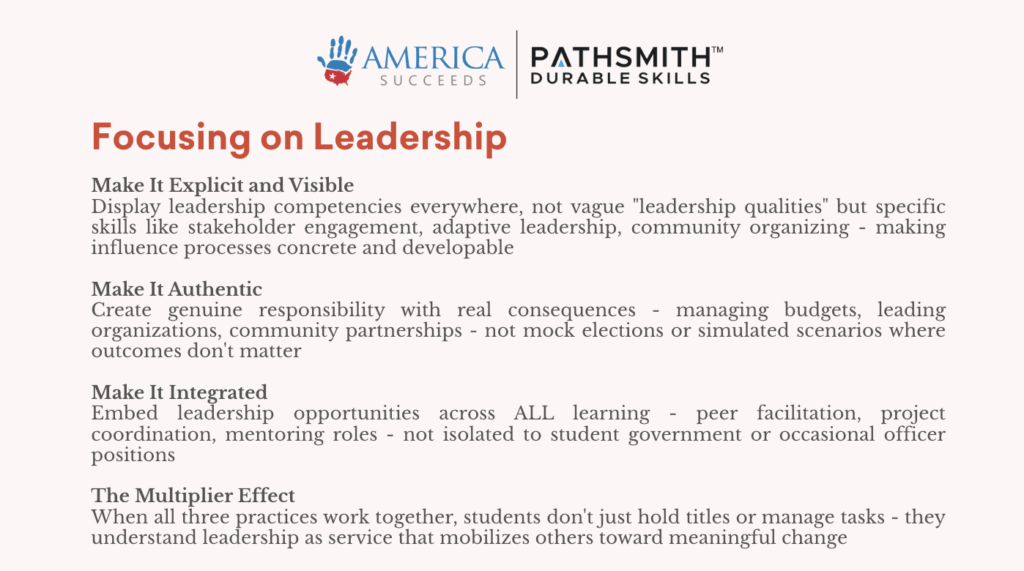

These schools reveal why leadership flourishes when three practices reinforce each other—and why traditional approaches that treat them separately achieve limited results.

Making leadership explicit gives students frameworks to understand what leadership actually looks like in practice. One Stone’s “Disruption Blob” and Batesville’s DISC assessment provide vocabulary and criteria that transform abstract notions of “being a good leader” into recognizable, developable competencies. When students can identify “stakeholder engagement,” “adaptive leadership,” or “community organizing” in their own actions, they can consciously cultivate these capabilities rather than hoping charisma emerges naturally.

Authentic experiences with genuine stakes motivate leadership growth beyond compliance. When One Stone students manage $2.1 million budgets or Batesville students lead businesses grossing hundreds of thousands, leadership shifts from academic exercise to essential practice. Traditional mock elections or simulated leadership scenarios produce surface-level skills. Real consequences—where communities, employees, or organizations depend on student decisions—create leadership necessity where growth becomes inevitable.

Integration throughout all learning provides constant reinforcement that develops leadership versatility across contexts. When leadership development embeds everywhere—from One Stone’s advisor relationships to Batesville’s work-based learning experiences—students develop the capacity to lead in any situation. Isolated leadership retreats or occasional officer positions can’t achieve this depth. The multiplication happens through progressive complexity: peer facilitation evolves into team coordination, then organizational management, finally community-wide influence where students discover they can shape the world around them.

Your Implementation Guide: Building Leadership Excellence

Getting Started:

Make Leadership Visible:

- Display leadership competencies on classroom walls and embed in daily practice, moving beyond generic “leadership qualities” to specific skills like “conflict resolution,” “strategic planning,” and “stakeholder engagement”

- Create leadership portfolios where students document their leadership journey—initial hesitations, growing confidence, specific situations where they influenced outcomes

- Have students create “leadership maps” showing their expanding circles of influence, from peer relationships, to family dynamics, to community impact

Create Authentic Experiences:

- Partner with local organizations that need genuine leadership from students—not token youth representation but real responsibility for outcomes

- Establish progressive leadership roles within your school where students manage budgets, coordinate events, mentor younger students, or represent the school in community partnerships

- Create failure-rich environments where students must navigate real consequences, learning that authentic leadership often emerges through overcoming significant challenges

Integrate Throughout Learning:

- Embed leadership opportunities in every subject—require students to facilitate discussions, teach concepts to peers, coordinate group projects with community partnerships

- Require leadership reflection in all major assignments where students identify when they influenced others, made strategic decisions, or took initiative beyond requirements

- Convert traditional presentations into leadership showcases where students demonstrate not just knowledge but their capacity to inspire and guide others toward understanding

The Significance of Leadership as a Life Skill

Leadership isn’t just about holding titles or managing others—it’s about developing the agency to create positive change wherever you find yourself. Students who learn to facilitate productive conversations can transform workplace dynamics. Those who understand stakeholder engagement become more effective parents, community members, and citizens. Young people who discover they can mobilize resources and coordinate complex initiatives realize they don’t have to wait for permission to solve problems they care about.

When schools systematically develop leadership through these three practices, they don’t just prepare students for future leadership roles. They develop young people who understand that leadership is fundamentally about service—recognizing needs, building coalitions, and persistently working toward solutions. This conscious development of leadership—rather than hoping it emerges naturally—prepares students not just for careers but for lives where they can shape their communities and contribute to positive change.

Next week: Growth Mindset: How schools transform fixed thinking into resilient learning through systematic mindset development.

Looking for K-12 durable skills resources to engage your students? Join the upcoming FREE PILOT to get early access!