America Succeeds defines Metacognition as the awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes, encompassing self-assessment, strategic planning of learning approaches, monitoring comprehension, and adjusting strategies based on reflection. It’s knowing not just what you know, but how you learn best.

Lauren sat with her advisor at Gibson Ek High School to review her Personal Learning Plan—a document serving as both “planning tool” and “guidebook for how I want my year to go.” Four years earlier, she’d approached learning mechanically: “I need X credits in math.” Now, as a senior, she articulated profound self-awareness: “After that design lab, I was like, okay, this is good information for me to have about myself and what kind of work I enjoy doing.” Following that, she focused on designing her experiences to do more of what she truly enjoyed doing. This wasn’t self-limitation but strategic adaptation.

Zoe met with her CAPS strand instructor Mark for her 18-week evaluation at Cedar Falls CAPS, reflecting on her transformed understanding of learning: “Something I learned in CAPS [this semester] was the importance of self-motivation. [Working] by yourself, it’s definitely harder to stay motivated because you don’t have as much structure. So I kind of had to create that structure for myself.” This recognition represents metacognitive sophistication rarely achieved – even in college.

These transformations reveal education’s most crucial capability: learning how to learn. Those who master this become self-teaching systems capable of acquiring any skill, adapting to any challenge, and evolving throughout their lives.

Gibson Ek High School: Personal Learning Plans as Living Documents

Gibson Ek makes metacognition explicit through sophisticated competency dashboards and Personal Learning Plans that serve as living documents of growth. Students continuously curate evidence of their competency development in both their digital portfolios and dashboards, connecting specific learning experiences to broader skill growth. Unlike traditional gradebooks obscuring learning behind letter grades, the dashboard displays growth through visual metaphors students understand. Kaia explained: “We have trees, and they grow. You check off different aspects of a competency, the more filled out the tree is.” To claim any competency growth, students must provide evidence—forcing deep thinking about what constitutes learning evidence.

The Personal Learning Plan serves as the metacognitive centerpiece, evolving continuously across four years. These documents contain personal inventories exploring learning styles, competency progress tracking with growth reflections, and experience documentation connecting internships to skill development. As students described, PLPs help them “nail down specific goals and what you really feel like you need to do.”

Lauren’s PLP evolution illustrates deepening self-awareness—from mechanical freshman compliance to sophisticated senior integration connecting STEM competencies to social justice work. This metacognitive problem-solving—recognizing what she wants to learn, how she wants to learn it, understanding capabilities, and designing learning experiences and pathways—demonstrates mastery beyond simply accumulating typical content knowledge.

To develop metacognition, Gibson Ek engages students in designing and pursuing interest-driven authentic learning experiences through self-designed personal learning projects, design labs, and internships. Sydney’s capstone project exemplifies this approach. Partnering with a veterinary microbiologist professor at Western University of Health Sciences, she designed research investigating veterinary mental health—addressing the profession’s high suicide rates. She coordinated interviews with first-year veterinary students across the country, collected their stories about mental health challenges during the transition from school to career, and planned presentations to veterinary schools to share findings. This demanded she employ sophisticated metacognitive strategies: actively monitoring her progress, continually questioning her research approach and revising it when useful, and mindful that she should seek out expert mentorship when needed, continually asking herself “How can I make this work both meaningful and impactful?”

Similarly, Connor’s internship at Midnight Motor Sports, a high end automotive design shop in West Seattle, evidences his metacognitive growth through real-world, authentic challenges. Working on vintage BMW restoration, he learned to diagnose complex mechanical problems, explain technical processes to customers, and document his learning through detailed portfolio reflections. When struggling to secure this automotive internship after numerous rejections, he developed metacognitive awareness about persistence and professional communication, coming to see rejection as data informing his approach, not personal failure, adjusting his strategy until successful. As his advisor Jef noted, Connor “worked his butt off, reached out to all these people and got a lot of no’s”—but learned a lot about how to engage others in being able to do what he wanted to do.

Gibson Ek integrates metacognition throughout learning via ongoing conversations and reflections with advisors, use of Personal Learning Plans, and exhibitions of learning held four times annually. Students present comprehensive exhibitions showcasing their learning journey—with the second exhibition each year taking the form of a design fair where students set up displays and engage visitors in conversations about their projects. These exhibitions require students to articulate their learning journey and growth over time, connect experiences to specific competencies, reflect on challenges and how they overcame them, and respond to questions from panels including advisors, parents, peers, and community members.

Lauren described how advisor conversations ground metacognitive development: “It’s a lot of like, hey, I know that you can do this more. I know that you can, like, I’ve seen you do this before, and I think that you can do it even better this time. And having these things to point to within our competency areas… he can point to that and say, hey, like, you have struggled with this, but I’ve seen development in that.” These conversations transform isolated experiences into visible patterns, helping students recognize their growth trajectories. Students regularly review their dashboards with advisors, analyzing which competencies need attention and designing projects to address gaps, making metacognitive planning a habitual practice.

The four-year advisory relationship enables metacognitive development over time. Jef articulated: “It’s really powerful to be able to work with a student for four years… you’ve done these things really well, and these things you’re growing on.” This longitudinal perspective transforms isolated experiences into visible patterns. Lauren’s crisis choosing a capstone project became a metacognitive breakthrough when her advisor helped recognize an overthinking pattern appearing throughout four years. The advisor could say, “Remember sophomore year when you had this same struggle? What worked then?” This historical perspective develops students’ ability to see patterns across time.

Cedar Falls CAPS: Performance Standards That Build Self-Awareness

CF CAPS makes metacognition explicit through their ongoing reflection on five performance standards evaluated every six weeks, each containing 10 specific skills. These standards—Globally and Competent Servant Leader, Effective Communicator, Finding Purpose, Emerging Innovator, and Developing Professional—aren’t external judgments but tools for guided self-assessment promoting deep metacognitive processing.

The value of reflection on standards extends beyond skill tracking. As Carson, a CF CAPS senior, explains: “I think that reflecting on yourself is one thing, but seeing what others notice about you is maybe entirely different. Both are equally as important.” El, another senior, noted: “We’re actually looking into… reflecting a lot and seeing how much we’ve improved. It’s not just for a grade… we’re actually hoping to improve on these types of things.”

Students write self-reflections prior to meeting with their strand instructor at 6, 12, and 18 weeks in the semester, identifying what Mark, the Business strand instructor, calls “aha moments”—instances where they’ve “either acquired a skill or developed a skill, and then they actually see that skill being utilized.” Critically, they then meet with instructors for coaching conversations. As TJ, the Career strand instructor, describes the process: “They do written reflections prior to when we meet with them, and then they have a post email to their parents about our discussion.” The rubric requires conscious understanding: reaching “Exemplary” means applying skills to “a complex, learning scenario unique to their CAPS experience.” As Zoe reflected after discovering her need for self-structure: “CAPS first semester was pretty self-driven… I’m kind of on my own, so I really have to push myself to get work done.”

To press for their learners’ development of metacognition, CF CAPS creates authentic professional experiences along with ongoing self-reflection revealing learning preferences through real-world client projects. One powerful example comes from Zoe’s first semester basketball video display project. Reflecting on its success, she discovered: “I personally thought that [it turned out well]. But also, like, a lot of my friends go to the basketball games… seeing other people’s reactions, like they obviously didn’t know it was me, so like seeing their reactions, I think, showed me that it was cool.” This external validation helped her understand the difference between internal standards and audience impact.

In Mark’s Business Solutions strand, one student reflected on waiting for project timing: “I think I was just waiting for, like, March Madness… which kind of slipped my mind.” Mark’s coaching response emphasized proactive help-seeking: “Don’t just sit there and sulk in the struggle. Like, ‘Hey, Mark, help me out here,’ and we can work on it together.” This recognition—that asking for help is strategic rather than weakness—represents sophisticated metacognitive awareness about learning processes.

Career discoveries—required for Standard 3 (Finding Purpose)—add another metacognitive dimension. Molly reflected: “I love the requirement of career discoveries… it significantly proved beneficial to me,” ultimately leading to her HANA Golf internship. These experiences reveal not just career interests but learning preferences through different professional environments.

CF CAPS integrates metacognition through immediate “retros,” ongoing reflection on the performance standards, and parent communication. Mark conducts 10-minute debriefs after every client meeting: “What went well? What didn’t go so well? What deliverables did you give your client? What do you know now that you need to implement?” As Mark observes: “I think a lot of it happens in the retro… The natural interaction, I think, is where the learning happens.”

Students must email parents after evaluations, recapping conversations and growth areas. Mark instructs: “You’ll write an email to your parents, you’ll CC me… Here’s a little bit about what I’m doing. Here’s some areas that I want to grow in the next six weeks.” This isn’t just communication—it’s metacognitive articulation reinforcing learning through explanation.

The Education strand provides compelling examples of metacognitive growth. Brianna, reflecting on CAPS Education, noted: “The biggest thing I’ve gotten out of it is just understanding who I am as a person. I’ve grown a lot, like, with a lot of different skills.” Similarly, James discovered through teaching freshmen: “Something that I’ve learned throughout CAPS is how to set boundaries, especially with kids, and like, working with them, and then also with my peers… making sure that we have a good professional relationship.”

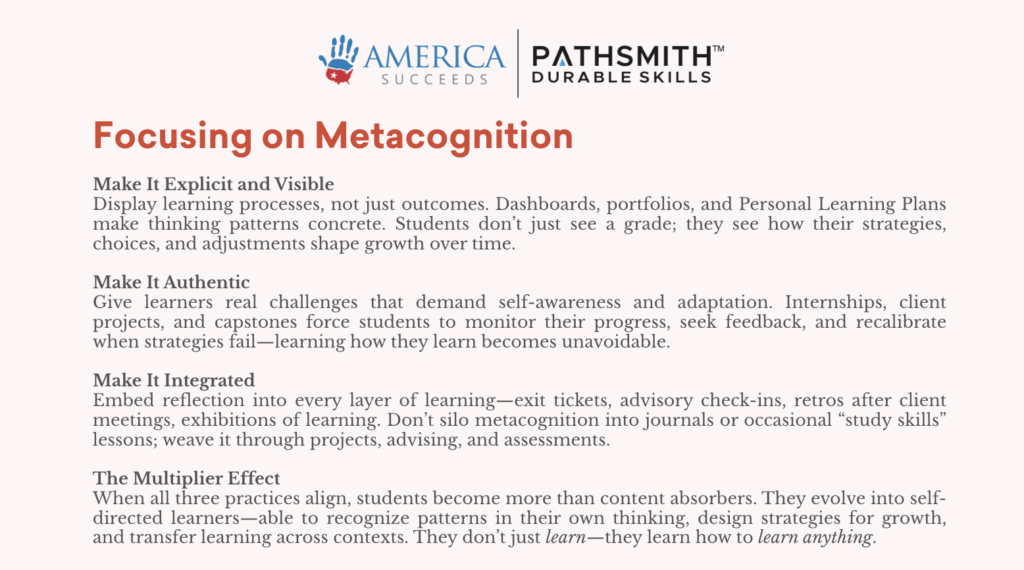

The Multiplier Effect: Why Metacognition Transforms

When schools systematically develop metacognition through these three practices, students transform from unconscious learners into conscious directors of growth. They develop “metacognitive fluency”—monitoring and adjusting learning strategies in real-time.

Gibson Ek’s Lauren evolved from mechanical freshman compliance to sophisticated strategic thinking. Cedar Falls CAPS’ structured progression reveals metacognition developing through systematic practice. Through repeated cycles of experience, reflection, and adjustment—marked by 6, 12, and 18-week evaluations—students develop consciousness about skill development.

The multiplication happens when explicit frameworks meet authentic experiences within integrated systems. Gibson Ek’s competency dashboard visual of trees growing, and four-year PLPs, make learning visible, while students’ personal learning projects and internships reveal how learning happens. Cedar Falls CAPS’ performance standards provide granular vocabulary for growth, while real client projects demonstrate where growth occurs.

Your Implementation Guide

Getting Started:

Make metacognition central through structured reflection protocols, visual progress tracking, and student ownership of learning documentation. Start small with exit tickets asking “What did you learn about how you learn today?” Build toward comprehensive portfolios tracking not just what students know but how they came to know it.

Make Learning Visible:

- Create competency rubrics with student-friendly language

- Require evidence portfolios documenting “aha moments”

- Use visual progress tracking systems students own

- Display learning objectives with daily self-rating

- Create “learning walls” for breakthrough insights

Create Authentic Experiences:

- Build 10-minute “retros” after significant experiences

- Schedule weekly coaching conversations about growth

- Film presentations for students to analyze thinking

- Implement peer teaching sessions

- Create comparative experiences revealing preferences

Integrate Throughout Learning:

- Embed reflection prompts in every assignment

- Make metacognitive language part of daily vocabulary

- Connect new learning to previous experiences explicitly

- Celebrate learning process discoveries enthusiastically

- Require “learning letters” to next year’s class

Build From What You Have:

- Add self-assessment to current rubrics

- Convert grading conferences to coaching sessions

- Turn test corrections into process analysis

- Transform parent conferences into student-led showcases

- Use group debriefs to explore collaboration insights

The Significance of Metacognition as the Meta-Skill

Metacognition isn’t just another skill—it’s the skill enabling all others. Students who understand how they learn can acquire any capability needed. In an era where knowledge becomes obsolete rapidly, this adaptability matters more than content mastery.

Metacognitive mastery transforms more than individual learning. Students understanding their own thinking patterns better understand others’, enabling deeper collaboration. They recognize when they’re stuck and seek help strategically. They transfer learning across contexts, seeing patterns others miss.

Most powerfully, metacognitive students become authors of their own education. As Lauren discovered, understanding “I’m not a very detail oriented person” isn’t limitation but liberation. As Zoe learned, recognizing differences between group and self-motivation allowed her to create needed structure. When schools develop metacognition through making it visible, creating authentic contexts, and integrating reflection, they develop young people capable of continuous evolution—prepared not just for next year’s class but for lifetimes of growth.

Next week: Growth Mindset: How schools transform fixed thinking into resilient learning through systematic mindset development.

Looking for K-12 durable skills resources to engage your students? Join the upcoming FREE PILOT to get early access!